Multiple myeloma

In plasma cells, mutations can occur wherein genetic alterations cause those cells to start to multiply excessively, but not stop producing antibodies. Since they all originate from a single, originally mutated "mother" myeloma cell and are its clones, these cells produce exactly the same type of antibody that is called a monoclonal protein. It can serve as a disease marker. The factors that promote development of plasma cell myeloma are unknown. The occurrence of the mutations described above is understood to be a random phenomenon.

Causes

Myeloma typically appears in people after the age of 60 and is preceded by a long pre-cancer condition called "monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS)". MGUS does not give any symptoms and the disease is detected accidentally based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and detection of monoclonal protein in the blood test. MGUS is quite common and many people live with it without being aware. In many cases myeloma never develops, so there are no indications for treatment, with regular checks being entirely sufficient. In further stages of the disease, the number of plasma cells in the bone marrow increases and the concentration of monoclonal protein in the blood is called "smouldering myeloma". The disease remains asymptomatic and can last several years in that form. In most patients there is no need for treatment. However, the control tests must be carried out more often in order to identify the moment of progression to the next stage, i.e. "symptomatic myeloma".

Symptoms

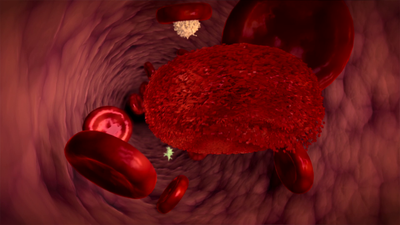

Myeloma symptoms are a consequence of excessive multiplication of plasma cells in the bone marrow. As the disease progresses, plasma cells fill the bone marrow, driving out production of normal blood cells. This usually causes anaemia, resulting from the insufficient number of red blood cells. Plasma cells also secrete substances that destroy bone tissue. This creates "holes punched out" by myeloma lesions, called osteolytic lesions. This can result in fractures that most often involve vertebrae and can cause severe pain. The monoclonal protein produced by plasma cells is also harmful. At its high concentrations in the blood, clogging of the kidney tubules and kidney failure can occur. Myeloma is also accompanied by a high susceptibility to infections that, without proper treatment, can be life-threatening.

Treatment

Treatment of myeloma aims at destroying as many plasma cells as possible in order to prevent or eliminate symptoms. Unfortunately, myeloma is so far considered an incurable disease. The aim is therefore to control the myeloma so that it does not affect the quality of life or life expectancy. However, since the therapy itself can have various side effects, it is only introduced once certain laboratory criteria have been met. Diagnosis involves blood and urine tests, bone marrow biopsies, and radiological examinations, e.g. computed tomography or whole body magnetic resonance imaging.

The myeloma is almost always generalized from its beginning and occurs in many parts of the body. Treatment must therefore be systemic and administered in the form of injections or oral medication. If there are lesions showing the risk of fracture or infiltrations compressing the spinal cord, radiotherapy and orthopaedic treatment may be useful. The first stage of treatment is the so-called induction. Usually three drugs with different mechanisms of action are used. The most common side effect of the treatment is neuropathy, manifesting itself in sensory disturbances in feet and hands. In most patients however, induction treatment is well tolerated. It is repeated periodically for about four months, typically without hospitalization. Usually it produces a response, such as a decrease in plasma cell numbers by half or more.

In people up to 70 years of age who have no other serious conditions, the next step is high-dose treatment, i.e. chemotherapy applied in very high doses for one or two days. This high-dose treatment allows for the deepening and maintaining of the response, but by destroying myeloma cells it also causes irreversible damage to normal bone marrow cells. Such therapy can only be used having previously collected hematopoietic stem cells. Those cells are harvested from patient's blood, after stimulation with appropriate drugs, using a cell separator machine and then frozen in liquid nitrogen vapour. After the treatment is completed, the cells are administered to the patient. The cells reach the bone and within about two weeks they replenish the destroyed bone marrow. The entire procedure is called autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. The transplant itself does not have a therapeutic effect, but enables application of chemotherapy in sufficiently high doses. In some myeloma patients, this procedure is often performed twice at an interval of 3 months. High-dose therapy is associated with the risk of life-threatening complications. This is especially true for the first two weeks, when the body is immunocompromised and therefore exposed to infections. Treatment should be carried out in special transplant wards, where appropriate preventive measures are applied.

Despite induction and high-dose therapy supported by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation, the disease can relapse after a varying amount of time. It is then necessary to introduce another line of treatment. Today, we have many drugs with different mechanisms of action that, when used in the case of relapse, usually allow for control of the disease and contribute to the lengthening of a patient's life. The average life expectancy of myeloma patients has doubled over the past decades.

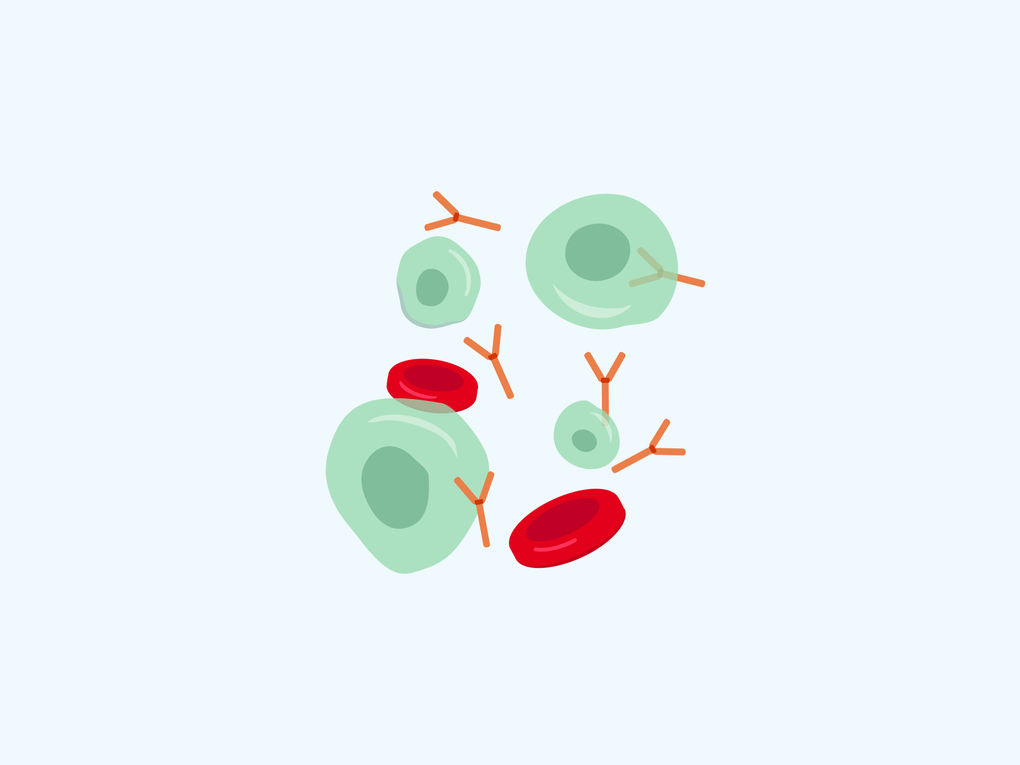

In young patients, whose myeloma is often more dynamic, transplantation of hematopoietic cells collected from another person may be considered. Such transplantation, called allogeneic, can lead to recovery. However, it is a riskier method and therefore rarely used in patients with plasma cell myeloma. There are high hopes in immunotherapy with genetically modified T lymphocytes known as "CAR-T cells". Its effectiveness is currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

Other diseases treated with hematopoietic stem cell

- Myeloproliferative disorders

- Myelodysplastic syndrome